Location: Home >> Detail

TOTAL VIEWS

Immunometabolism. 2020;2(2):e200016. https://doi.org/10.20900/immunometab20200016

1 Department of Pediatrics, Ian Burr Division of Endocrinology and Diabetes, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 37232, USA

2 Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN 37232, USA

* Correspondence: Daniel J. Moore, Tel.: +1-615-322-7427; Fax: +1-617-724-7165.

This article belongs to the Virtual Special Issue "Immunometabolism in Autoimmune Diseases"

Although B lymphocytes are a key cell type that drives type 1 diabetes (T1D), therapeutic targeting of these cells has not ameliorated disease, and it has been impossible to eliminate autoantibody production clinically once it begins. This challenge indicates a need for further dissection of the cellular processes responsible for the development and activation of autoreactive B cells in T1D. Review of the literature in T1D and other autoimmune and hematopoietic diseases indicates that cellular metabolism contributes significantly to lymphocyte development and fate. Unfortunately, little is known about the normal metabolism of B cells and even less is known about the metabolism of B cells in T1D other than what can be inferred from other immune processes. Clues derived from the literature suggest B cell metabolism in T1D is altered including potential differences in OXPHOS, glucose metabolism, fatty-acid metabolism, and reactive-oxygen species stress response. Future research should dissect the metabolic processes at play in autoreactive B cells in T1D. Once understood, B cell metabolism will become a promising target to use in conjunction with current clinical therapies in T1D. Additionally, metabolic changes in B cells may serve as a reliable biomarker for predicting the responsiveness of patients to these immune therapies.

Lymphocytes are subject to regulation by intrinsic and extrinsic metabolic parameters. While the metabolism of T cells is well described and has been targeted in pre-clinical models to impact immunity, the metabolism-dependent regulation of B lymphocytes (B cells) is less well understood [1–6]. At baseline, naïve B cells have very little metabolic activity, a condition that may be important for preventing improper activation of these cells. Indeed, at rest, B cells possess decreased mitochondrial numbers compared to T cells and may possess the least amount of mitochondria among the hematopoietic lineage [7,8]. Upon stimulation B cells increase oxidative phosphorylation, glucose uptake, the citric acid cycle (TCA), and nucleotide biosynthesis [7]. Early work indicated that glucose utilization is important for activation and survival of B cells, similar to their T cell counterparts. While the fate of this glucose was thought to be glycolysis, a new study indicates that the glucose may be utilized for nucleotide biosynthesis over glycolysis [7,9,10]. Contrasting with earlier research, this paper indicates glucose restriction, but not complete removal, did not impact initial B cell activation and proliferation. However, other studies have indicated glucose does limit the capacity for B cells to form germinal centers and produced class-switched antibodies [4,7]. As B cells have multiple functions besides antibody production, it will be important to determine what role glucose plays in antigen capture, presentation, trafficking and survival in addition to B cell activation, expansion, and antibody production.

These properties make B cells unique compared to T cells when evaluating pathways and targets for metabolic modulation of immune function and indicate a need for specific understanding of B cell metabolism to advance immune therapies. Indeed, studies in T cells have begun to elucidate the metabolic parameters that are important for T effector and T regulatory function, but a similar paradigm has not been established in B cells [1].

This review discusses the role of immune metabolism in B cells in autoimmune disease, with a focus on type 1 diabetes (T1D). Although the autoimmune pathology in T1D is driven by T cells, B cells are critical for autoreactive T cell activation making the function of B cells a critical node in disease pathogenesis [11–16]. Attesting further to the central role of B cells in disease, anti-islet autoantibodies have long been recognized as the signature of impending and new-onset disease. The presence of these autoantibodies is now a diagnostic criterion of T1D well in advance of the appearance of clinical hyperglycemia [17]. Clinically, targeted B cell depletion has delayed loss of insulin production in patients with new-onset disease, but unfortunately disease progression returns once B cells repopulate [12,15,18]. Little is known about the B cell intrinsic metabolic processes that drive autoimmunity in T1D, and it has not been considered whether metabolic abnormalities play a role in the reemergence of beta cell destruction after B cell directed therapy. This review will examine the metabolic regulation of normal B cell development and activation, review evidence suggesting dysmetabolic features of B cells in T1D, and highlight opportunities for metabolic interventions to regulate the B cell response to halt disease progression.

B cell development begins in the bone marrow, where approximately 70% of B lymphocytes generated possess an autoreactive specificity [19]. The detection of autoreactive Ig receptor expression triggers either receptor editing or deletion; cells surviving these initial selection steps emerge to the spleen to complete development. At maturation, approximately 25% of the naïve mature B cell population demonstrates hallmarks of receptor editing, indicating replacement of autoreactive receptors with protective immunoglobulins during development to permit continued cell survival [20]. Autoreactive cells that persist after these successive steps in development are thought to undergo anergy in healthy people, rendering them nonresponsive to their cognate antigen [20]. B cells that display non-autoreactive specificities become naïve cells and will activate following antigen encounter leading to production of antibodies of varying affinity and class, depending on the context. Throughout these stages of development and activation, B cell metabolism varies to adapt to the individual metabolic need of each stage. Overall the metabolic requirements of B cells and the metabolic influences on B cell development and activation are poorly understood. Understanding these differences will be important in determining how to influence B cell development and activation and may become part of targeted strategies to prevent and reverse autoimmune disease.

Early B Cell Development Is Marked by Metabolic Requirements for ProliferationB cells begin their life in the bone marrow, arising from hematopoietic stem cells before entering the common lymphoid progenitor compartment. The pre-pro B cell represents the earliest stage of B cell commitment and is marked by the expression of Ikaros, PU.1, E2A, EBF-1, and Pax-5 [21]. These cells do not express recombinase-activating gene (RAG) and thus possess both the heavy and light immunoglobulin chain (IgH and IgL) gene loci in their germline configurations. The metabolic demands of these cells remain mostly unknown but are likely dependent on IL-7 signaling acting through both STAT and Akt-dependent pathways. While little is understood about the metabolic processes, pre-pro B cells should possess a significant metabolic demand due to their rapid proliferation.

These cells migrate towards their developmental niches within the bone marrow due to CXCL12 chemokine signaling and expression of CXCR4, where they develop into large pro-B cells [22]. These cells are acutely dependent on IL-7 to prevent apoptosis and induce proliferation [22,23]. At this stage, pro-B cells utilize glycolysis; studies in T cells suggest this utilization is most likely due to the action of IL-7 on the Akt pathway. Additionally, B cells at this stage enhance oxidative phosphorylation [24–26]. Phosphorylation of c-Abl peaks during this time in B cell development indicating an important role for c-Abl in this developmental stage [27]. Other studies have demonstrated that c-Abl activation increases glucose uptake in B cell cancers, suggesting it may also do so here to help developing B cells avoid apoptosis [28]. At the end of the pro-B cell stage, Rag1 and 2 are activated to allow for the recombination of V, D, and J regions of the heavy chain locus. Successful recombination of the heavy chain locus leads to surface expression of the heavy chain paired with a surrogate light chain forming the pre-BCR. This event marks the transition from pro- to pre-B cell, concomitant with a loss of IL-7 sensitivity [24,29]. The change from IL-7R dependency to pre-BCR signaling represents the first step in a developmental switch that places much of the metabolic signaling downstream of the BCR [30–33].

Establishment of the pre-BCR facilitates the ability of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) to signal through PI3K and Erk pathways allowing large Pre-B cells to undergo a proliferative burst associated with metabolic upregulation of both glucose uptake and mitochondrial activity [30,33–36]. After this initial proliferative burst, the cells enter the small-pre-B stage marked by reactivation of Rag 1 and 2 to allow VJ recombination of the light chain gene locus [37]. Studies in pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) suggest that Pax5, EBF1, and Ikaros may be responsible for downregulation of metabolic genes to pause the cell cycle and allow for proper recombination of the light chain to occur [38]. Additionally, Foxo1, a gene activated by metabolic deprivation, is essential for activation of Rag1/2, further suggesting robust metabolic changes may occur at this stage [23,39,40]. Experimental observations demonstrate a downregulation of glucose uptake and decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS production at this stage [33]. While there is an overall reduction in energy consumption, these cells seem to favor OXPHOS, but the preferential metabolic substrate remains to be determined.

Immature B cells are subject to selective pressure if they encounter their cognate antigen [19]. If the initial heavy and light chain pairing is directed against a self-antigen, then antigen encounter will trigger the immature B cell to recombine its second light chain locus and express a newly paired BCR [41]. If this BCR is also autoreactive, then the cell will undergo apoptosis resulting in negative selection [42]. Studies of the WEHI-231 immature B cell line indicate this process is regulated in part by breakdown of the mitochondrial membrane potential [43]. While calcium signaling perpetuated from the BCR leads to activation of caspases to mediate cell death, changes in mitochondria precede the death of B cells induced by BCR signaling at this stage and may further exacerbate changes in intracellular calcium handling [42,44–46]. The mechanism of loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and its metabolic consequences in B cells remains poorly understood but may be regulated by the Bcl-2 family of proteins leading to changes in ion pores in the mitochondria [44–49]. Another intriguing mechanism of mitochondrial collapse in B cells is the accumulation of arachidonic acid or ceramide in the mitochondria due to activation of mitochondrial phospholipase A2 (PLA2) [43,50]. The change in the lipid profile in the mitochondrial membrane can alter membrane integrity and permeability, providing a link between lipid metabolism and B cell selection. Like the preceding stage, immature B cells are metabolically quiescent and the primary metabolic substrate that is utilized is undefined [51].

After completion of these bone marrow developmental stages, B cells exit the bone marrow and enter the spleen, where they are subjected to continued negative selection in the transitional B cell compartment before entering the mature compartments [52]. Virtually nothing is known about the metabolic requirement of these transitional B cells and how metabolic changes may impact negative selection, although this is the key stage that prevents maturation of autoreactive B lymphocytes. Once matured, B cells are composed of two main compartments, B1 (often referred to as peritoneal B cells) and B2 (traditional splenic B cells) [53]. B1 B cells are found in small quantities in the spleen and are mostly localized to the peritoneal cavity; it is unclear whether these cells arise via the same developmental pathway as B2 B cells [54,55]. These cells produce non-induced IgMs often against polysaccharide targets [56]. This activity is most likely metabolically demanding, and thus these cells demonstrate enhanced metabolism and a dependence on glycolysis [56]. B2 B cells demonstrate metabolic inertness as compared to their B1 counterparts, demonstrating utilization of fatty-acid (FA) as their oxidative fuel source [57]. There appears to be a reduction in the ratio of ATP to AMP indicating resting B cells are in a state of energy deprivation that is thought to be maintained via LKB1/AMPKa signaling axis [38,58]. B2 B cells are divided into two classes, marginal zone and follicular zone B cells [53]. The follicular zone B cells are responsible for producing high-affinity class-switched antibodies upon activation while the marginal zone B cell produces natural antibodies in a T-independent manner much like B1 B cells, but thus far no differences have been demonstrated in their metabolic needs or activity [59]. While no overt differences in metabolism have been defined between these two cell subsets, studies of human transitional B cells indicate that the maturation to follicular zone B cells induces downregulation of the mTOR/Akt signaling pathway as well as other metabolic pathways [60]. Marginal zone B cells seem to be reliant upon the action of mTOR/Akt signaling as genetic loss of this pathway leads to a reduction in this cell type [61–64]. Additionally, marginal zone B cells require Notch2 signaling to differentiate [65,66]. In activated T cells Notch signaling has a complex interaction with glutamine metabolism in the control of IL-2 production [67]. Notch signaling may provide the capacity to modulate function in the case of limited nutrients, and this interaction may distinguish marginal zone and follicular B cell function, but further investigation is needed.

B Cell Activation Leads to Increased Metabolism and Generation of ROS for Proper B Cell FunctionUpon activation, B cells upregulate metabolic processes, a function dependent on the action of c-Myc [57]. A recent study has clarified the metabolic processes that occur during B cell activation and how they differ from T cell activation. An unbiased approach utilizing RNA seq and analysis of mitochondrial morphology revealed that, upon activation by their cognate antigen or via TLR signaling through LPS, B cells begin to upregulate OXPHOS and extensively remodel the mitochondria to support increased ATP production [7]. Surprisingly, tracking of a glucose isotopomer revealed that the majority of glucose was shunted towards the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) and towards the pentose phosphate pathway for ribonucleotide synthesis, but not glycolysis [7]. Corroborating these results, glucose restriction did not impact the activation or proliferation of B cells while inhibiting OXPHOS or glutamine metabolism severely crippled B cell activation [7]. Previous work on B cell activation indicated an increase in glycolysis in activated B cells [57]. Indeed, one of the major functions of B cells, antibody production, depends on proper glycosylation of the produced immunoglobulins to sustain structural stability, promote immune regulation, and bind Fc receptors [68–71]. The substrates utilized for glycosylation are often shared with energy-producing glycolytic pathways, indicating a greater need for flexible glucose metabolism in relation to antibody production and function and the potential that changes in these pathways could alter B cell effector or regulatory function [72,73].

Anergic, Autoreactive B Cells Cannot Upregulate Metabolism after StimulationSome autoreactive B cells escape negative selection during development and persist to maturity. In healthy individuals these cells are speculated to be continuously occupied with self-antigen [74]. This tonic signaling is thought to render these cells “anergic”, a condition in which these cells are unresponsive to further stimulation and thus unable to mount an effective response against their cognate antigen [74]. To recapitulate and analyze the metabolism of an anergic B cell, researchers studied B cells from double transgenic mice that expressed both anti-HEL B cells and the HEL antigen. B cells from these mice demonstrated metabolic impairment in both glycolysis and OXPHOS compared to B cells from mice possessing only the BCR in the absence of antigen [57]. This observation indicates that anergy depends, in part, on restricting metabolism to prevent activation. The signaling pathways and timing of signaling that drives and maintains metabolic anergy in B cells still needs to be dissected and it is not known whether enforcing limited access to nutrients could enhance anergy induction to address autoreactive cell activation.

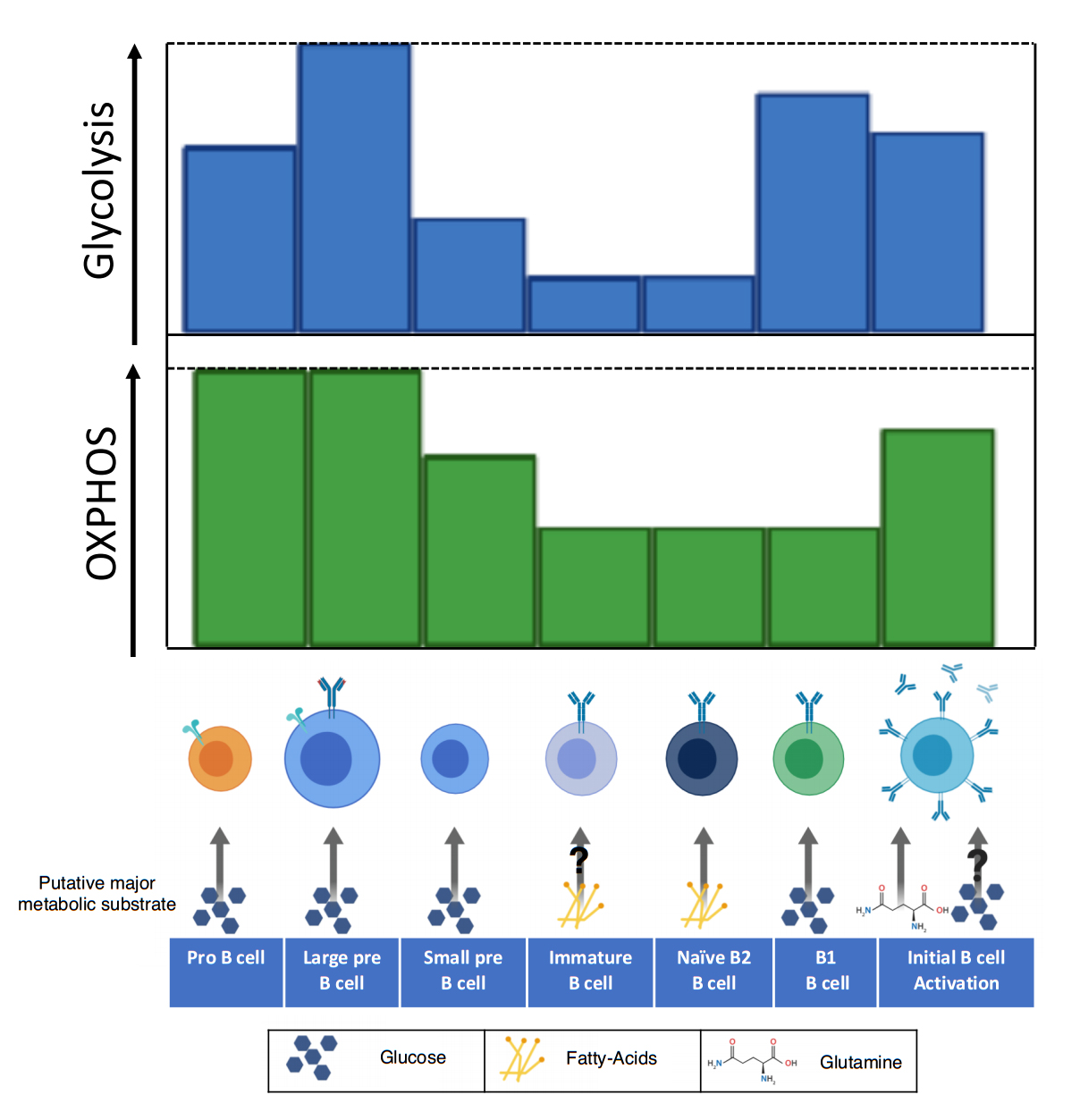

Summary of Normal B Cell Metabolism and Caveats to B Cell Metabolism ResearchThis synopsis of normal B cell metabolism sets the framework for dissecting the ways in which B cell metabolism interacts with B cell development and selection, and how metabolism may be important for the development of B cell driven autoimmune disorders. It is worth noting that the isolation of distinct pro-B cells and pre-B cells in sufficient numbers for metabolic analysis is difficult in wild-type mice. Many of the studies that define the metabolic state of these cells are carried out in knockout mice that develop blocks in B cell development due to loss of critical transcription factors. As B cell development is a dynamic process and driven by the availability of homeostatic factors, it is possible that a block in B cell development may have unintended consequences on B cell metabolism. In mature B cells, as in T cells, many of the metabolic requirements have been determined by utilizing compounds that block metabolic pathways in an ex vivo system. These inquiries suffer from both the lack of specificity (i.e., the compounds have off-target effects that impair other aspects of cell function) and the cells are tested in a condition of hyper-nutrition that may not recapitulate the in vivo reality. Nonetheless, these are the best data available for B cell metabolism and indicate the need for more research into the metabolic underpinnings of B cell development and function. A summary of what is currently known about B cell metabolism across development is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The utilization of oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis varies throughout the development of B cells. Early in B cell development (pro-B), the metabolic demand is high as developing B cells rapidly proliferate. In this stage both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation are increased, largely due to the action of IL-7 signaling. The large pre-B cell has enhanced glycolysis and OXPHOS, which may be due to an initial signaling burst from the pre-BCR. Downregulation of the pre-BCR to allow for recombination of the light chain blunts metabolism, a trait that is carried until reactivation of the B cell. Once a complete BCR is expressed, the immature B cell possesses reduced metabolism and may be dependent on fatty-acids as its primary metabolic substrate. Naïve B2 B cells maintain reduced metabolism and dependence on fatty-acid metabolism. Individual metabolism of B2 B cell subsets including the follicular and marginal zone remains unknown. B1 B cells, which reside primarily in the peritoneal cavity, depend largely on glycolysis for survival. Upon activation, B cells upregulate glucose uptake and remodel their mitochondria. There are conflicting reports on whether glucose is utilized in glycolysis or for the production of nucleotides. This disparity may be due to the changing role of glycolysis between early and late B cell activation and should be clarified by further studies. The amino acid glutamine is the primary metabolite utilized in OXPHOS for B cell activation and proliferation.

Figure 1. The utilization of oxidative phosphorylation and glycolysis varies throughout the development of B cells. Early in B cell development (pro-B), the metabolic demand is high as developing B cells rapidly proliferate. In this stage both glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation are increased, largely due to the action of IL-7 signaling. The large pre-B cell has enhanced glycolysis and OXPHOS, which may be due to an initial signaling burst from the pre-BCR. Downregulation of the pre-BCR to allow for recombination of the light chain blunts metabolism, a trait that is carried until reactivation of the B cell. Once a complete BCR is expressed, the immature B cell possesses reduced metabolism and may be dependent on fatty-acids as its primary metabolic substrate. Naïve B2 B cells maintain reduced metabolism and dependence on fatty-acid metabolism. Individual metabolism of B2 B cell subsets including the follicular and marginal zone remains unknown. B1 B cells, which reside primarily in the peritoneal cavity, depend largely on glycolysis for survival. Upon activation, B cells upregulate glucose uptake and remodel their mitochondria. There are conflicting reports on whether glucose is utilized in glycolysis or for the production of nucleotides. This disparity may be due to the changing role of glycolysis between early and late B cell activation and should be clarified by further studies. The amino acid glutamine is the primary metabolite utilized in OXPHOS for B cell activation and proliferation.

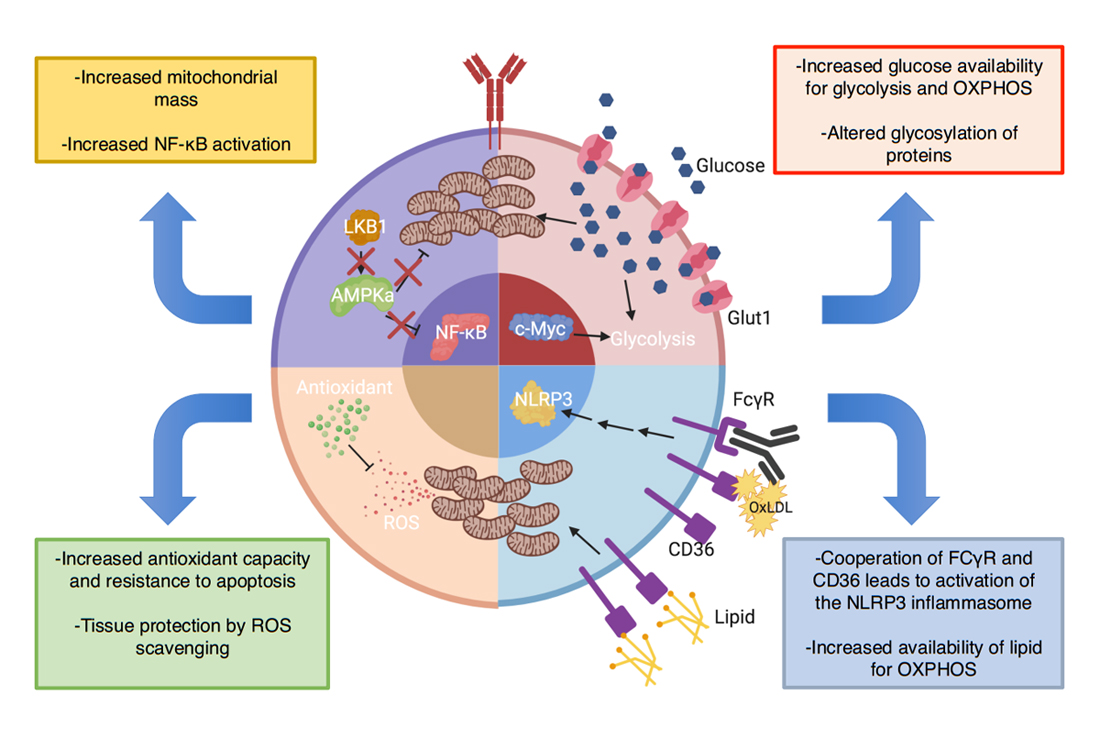

Scant data exists for the metabolic state of mature naïve B cells in T1D. The healthy resting B cell seems to be in a state of energy deprivation as illustrated by a decrease in the amount of ATP and an increase in the amount of cellular AMP. This imbalance of the AMP to ATP ratio indicates increased activity in the LKB1/AMPKa pathway in B cells [38,58]. The result of this seemingly chronic activation of LKB1/AMPka is apparent in the reduced number of mitochondria relative to other cells of the hematopoietic lineage [8,75]. These small, fused mitochondria are relatively inert and do not produce significant levels of ATP [7]. Interestingly, LKB1 opposes the activity of NF-kB, a pathway that is upregulated in B cells in the NOD (non-obese diabetic) mouse, the primary preclinical model of T1D, and thought to contribute to T1D pathophysiology [76,77]. Dysregulation of the LKB1/AMPKa pathway could lead to increased mitochondrial mass in T1D and leave B cells poised for metabolic priming with even suboptimal signaling. Clinically, targeting this abnormal process with metformin could potentially correct LKB1/AMPKa signaling and reduce NF-kB signaling and warrants further investigation (see Figure 4).

T1D B Cells Have Increased Levels of Lipid Scavenger CD36 Indicating Enhanced FA MetabolismWhile oxidative metabolism is important for activated and naïve resting B cells alike, naïve B cells seem to rely on FA as their main fuel source [57]. Dyslipidemia is a characteristic of T1D, but it is generally thought to be a result of hyperglycemia and insulin deficiency after disease onset [78,79]. However, studies of the NOD mouse metabolome in pre-diabetic mice indicated changes in the lipid profiles including increases in triglycerides in mice that progress to diabetes compared to those that are protected [80]. By comparison, B cells in high-fat diet fed mice demonstrate general immune activation, produce more IgG and less IgM, and increase whole body insulin resistance, indicating a role for altered lipid metabolism in immune activity that corresponds with features of the NOD mouse [81]. In NOD mice our lab demonstrated that B cells possess enhanced expression of CD36, a fatty acid translocase (FAT) [82]. Upregulation of lipid scavenger CD36 correlated with an increased propensity for B cells to take up BODIPY-labeled linoleic acid (unpublished data). This increased affinity for lipid metabolites via upregulation of lipid scavenger CD36 may impact the activity of B cells. While fatty-acids are important for B cell metabolism, it remains unknown the consequence of enhanced uptake of fatty-acids by B cell-expressed CD36, which has the highest affinity for oxidized-low density lipoproteins (oxLDL) [83]. Uptake of oxLDLs enhances inflammation in many cell types, including B cells [84]. Interestingly, oxLDLs are often found complexed with immunoglobulins [85]. Normally, binding of circulating immunoglobulins to Fc-receptors on B cells inhibits these cells by activation of SHIP [86,87]. When oxLDLs are complexed with immunoglobulins and internalized, this process activates the NLrp3 inflammasome in bone marrow derived dendritic cells, a process dependent on TLR4, CD36 and Fcgamma receptor signaling [85,88]. This interaction could lead to escape of B cells from IgG mediated inhibition. This observation justifies the need for investigation into the role of circulating nutrients as an environmental trigger in at least some patients with T1D. The role of lipids as an inciting event in humans with T1D is presently unknown but changes in weight gain and growth patterns have recently been associated with diabetes risk [89].

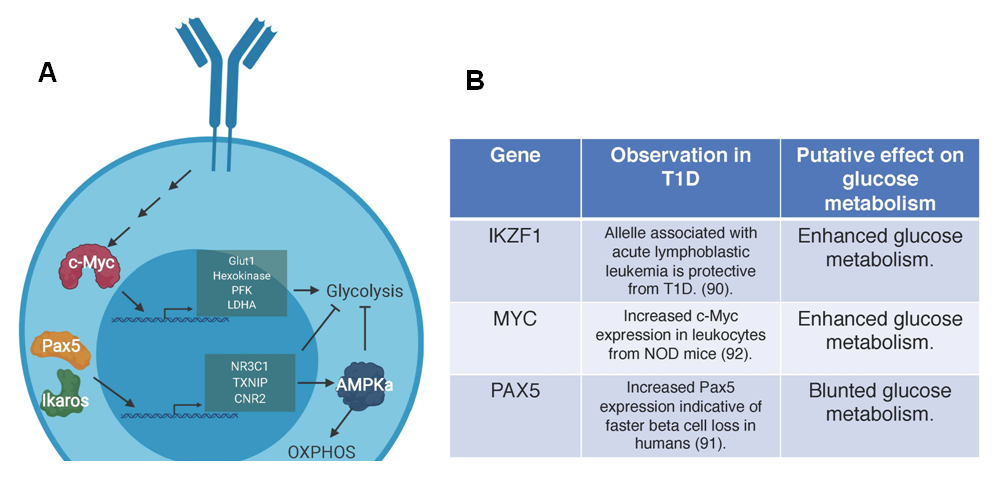

Genes Involved in Regulation of Glucose Metabolism Are Abnormal in T1DGlucose metabolism is low in naïve cells, but once activated or transformed, B cells utilize glucose largely through the Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) [7]. In naïve B cells the transcription factors Pax5, EBF1, and Ikaros control B cell lineage commitment as well as maintain low glucose flux, presumably by regulating both Glut1 and the insulin receptor [38]. Changes in these critical control elements may change the tempo of progression to type 1 diabetes. One study indicated an allele of Ikaros that is associated with susceptibility to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia may protect from T1D [90]. The idea that an allele of a gene that presumably supports enhanced metabolism characteristic of leukemia would slow progression of autoimmunity stands in opposition to common models for the role of T cell metabolism during autoimmunity [6]. Additionally, upregulation of Pax5 predicted faster progression of beta cell destruction in patients with T1D as found in comparison between subjects with rapid loss of insulin production to those who had slower loss [91]. The data indicate that genes that restrict glucose metabolism in B cells may actually be detrimental to T1D disease progression.

Alternatively, evidence suggests that enhanced glucose utilization may also be a characteristic of T1D. During B cell activation, c-Myc ramps up metabolism including glucose uptake and glycolysis [57]. Studies from isolated total leukocytes from prediabetic NOD spleens indicated early changes in metabolic pathways, as compared to healthy control mice. c-Myc was among these upregulated genes [92]. Additionally, c-Myc is upregulated in response to glucocorticoids in T cells from NOD mice, thus preventing apoptosis through a mechanism that has been related to increasing glycolytic metabolism to subvert apoptosis in other cell types [93,94]. These findings indicate the possibility for altered lymphocyte glucose metabolism in the pathogenesis of T1D. Whether c-Myc plays a role in glucose metabolism in B cells from T1D remains to be seen. These genes and their putative role in B cells in T1D are outlined in Figure 2; given the potential contrasting roles performed by glucose utilization, it remains critical to understand the metabolic demands of B cells throughout normal development and in relation to T1D progression.

While healthy B cells seem to favor OXPHOS and nucleotide biosynthesis as downstream products of glucose metabolism, excess glucose uptake in T1D B cells may feed into glycolysis. The nutrient excess may lead to cellular stress and inappropriate B cell activation. As n-glycosylation of proteins is integrally linked to glucose metabolism, changes in glucose metabolism may drive aberrant glycosylation patterns that could hinder appropriate cell-cell communication and alter antibody production or function. Naturally-occurring IgMs have recently been determined to maintain immune regulation, and this activity has been linked to its glycosylation pattern [95–101]. Abnormal glucose utilization could lead to improper glycosylation of IgM and loss of its regulatory capacity. We have recently determined that IgM from NOD mice do not possess the same capacity to properly regulate B cell homeostasis, Treg function, and prevention of T1D as compared to healthy control animals [102]. How IgM glycosylation drives this failure in immune regulation and how it can be corrected remains to be determined. Additional research will need to be conducted to understand the developmental stages during which abnormal metabolism acts to accelerate B cell pathology in T1D.

Figure 2. Genes involved in the regulation of glucose in B cells. (A) The genes and related pathways outlined here have been associated with glucose regulation in B cells. Pax5 and Ikaros oppose glycolysis and enforce OXPHOS through transcriptional control of genes NR3C1, TXNIP, CNR2 to restrict cellular nutrients and activate APMKa at multiple steps of B cell development. In normal B cell activation, c-Myc regulates the expression of multiple proteins involved in glycolysis including glucose transporter 1 (Glut1), hexokinase, phosphofructokinase (PFK), and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA). (B) Studies in humans indicate that an allele of Ikaros (IKZF1) that is associated with oncogenesis and potentially enhances glycolysis offers protection against T1D. c-Myc (MYC) activity is elevated in mice with T1D and may drive enhanced glycolysis, which is potentially harmful for immune regulation. Increased Pax5 (PAX5) expression in humans leads to enhanced beta cell loss. This gene list and putative effects on disease progression indicate a need to reconcile the potential differences in B cells in murine models and humans. Future studies should define what developmental stage these genes act on to induce metabolic derangement in B cells in T1D.

Figure 2. Genes involved in the regulation of glucose in B cells. (A) The genes and related pathways outlined here have been associated with glucose regulation in B cells. Pax5 and Ikaros oppose glycolysis and enforce OXPHOS through transcriptional control of genes NR3C1, TXNIP, CNR2 to restrict cellular nutrients and activate APMKa at multiple steps of B cell development. In normal B cell activation, c-Myc regulates the expression of multiple proteins involved in glycolysis including glucose transporter 1 (Glut1), hexokinase, phosphofructokinase (PFK), and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA). (B) Studies in humans indicate that an allele of Ikaros (IKZF1) that is associated with oncogenesis and potentially enhances glycolysis offers protection against T1D. c-Myc (MYC) activity is elevated in mice with T1D and may drive enhanced glycolysis, which is potentially harmful for immune regulation. Increased Pax5 (PAX5) expression in humans leads to enhanced beta cell loss. This gene list and putative effects on disease progression indicate a need to reconcile the potential differences in B cells in murine models and humans. Future studies should define what developmental stage these genes act on to induce metabolic derangement in B cells in T1D.

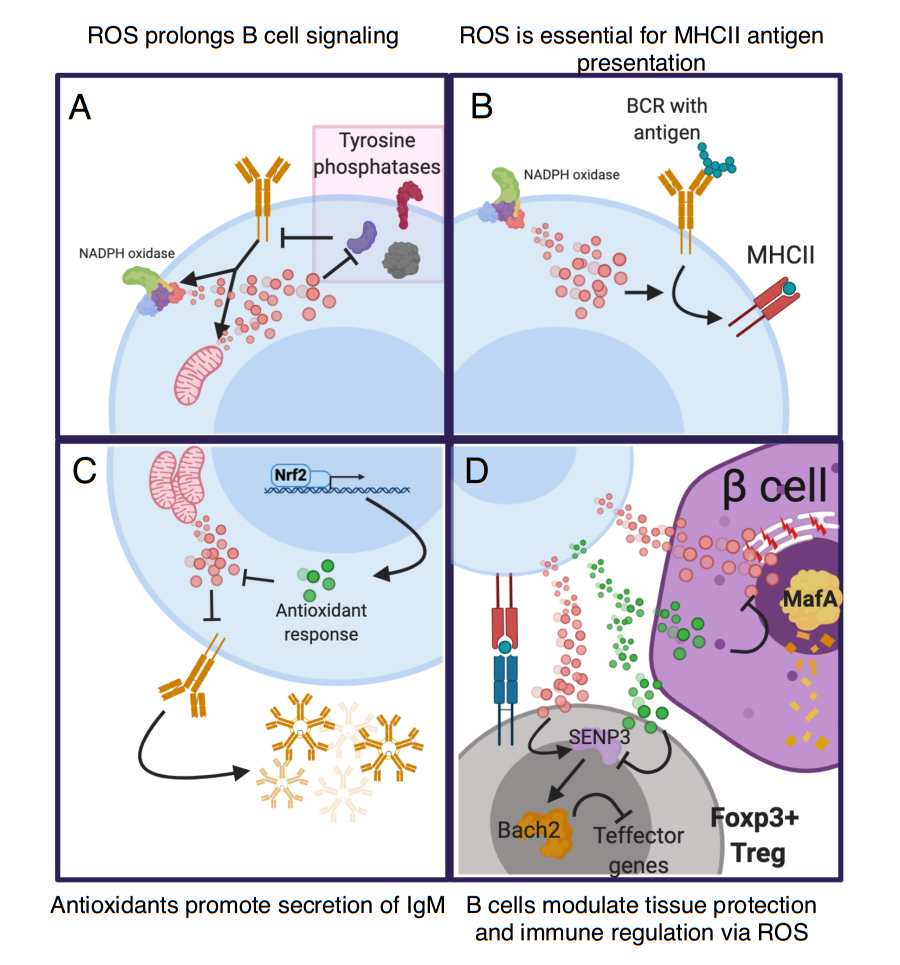

Along with changes in metabolism, increased oxidative metabolites were found in the circulation of NOD mice that rapidly progressed to disease indicating increased oxidative stress as suggested in the previous section [80]. B cell receptor mediated production of ROS is important for proper activation and function of B cells [103,104]. This ROS modulates signaling pathways by transiently inhibiting phosphatases to enhance and prolong signaling (outlined in Figure 3A) [105]. While increased ROS production may lead to aberrant immune activation and autoimmunity, operating under continuous extrinsic and intrinsic oxidative stress could lead to cellular apoptosis in immune cells unless a strong antioxidant system is in place.

Although B cells require ROS for full activation, increased ROS production drives apoptosis in certain stages of immature B cells [106]. An excessive antioxidant response could lead to the survival of autoreactive B cells that are receiving antigen stimulation during steps in negative selection. An increased antioxidant response, as we have observed in NOD B cells, would potentially support the production of autoantibodies in T1D and the perpetuation of an autoreactive cell population that might not normally produce a long-lived antibody response [107]. This initial investigation indicated that this antioxidant capacity was likely due to the action of the superoxide dismutase system (SOD1 and SOD2) and not through the glutathione peroxidase (GPx) [107]. This enhaced oxidative protection may be an intrinsic characteristic of all B cells in NOD mice or may be a consequence of some stage of negative selection in which only those cells with the greatest capacity to resist ROS-induced apoptosis survive.

Figure 3. Reactive-oxygen species (ROS) metabolism is important in many aspects of B cell function. ROS enhances the immune response and causes direct damage to pathogens and other cells that lack antioxidant capacity. Intracellular ROS modulates B cell function in many ways. (A) Upon B cell activation, BCR signaling triggers ROS production via the mitochondria and NADPH oxidase 1 (NOX1) complex. This ROS reversibly oxidizes tyrosine phosphatases to limit their ability to dephosphorylate target kinases. This action prolongs and enhances BCR signaling [104,108]. (B) Antigen internalization and presentation is an essential function of B cells and is modulated by production of ROS via NOX1. This production is key for the ability of antigens internalized via the BCR to be presented on the cell surfaces via Major-histocompatibility complex II (MHCII). Interestingly, ROS does not impact the presentation of intracellular derived antigens [103]. (C) After activation ROS opposes the capacity of B cells to secrete immunoglobulin. Nrf2 promotes IgM secretion by increasing antioxidant genes to oppose ROS [109]. (D) Both ROS and antioxidants that emerges from B cells impact bystander cells. B cells that present antigen to Tregs could transfer ROS to Tregs thus enhancing Tregs via the action of SENP3 and Bach2 [110]. Conversely, a B cell with enhanced antioxidant capacity may prevent ROS-mediated activation of SENP3 and thus inhibit Tregs. The action of B cells may also mediate tissue protection in cell types sensitive to ROS, like beta cells. Under certain circumstances B cells can upregulate antioxidant capacity that can be transferred to the extracellular space (green dots). This transfer prevents degradation of ROS-sensitive beta cell transcription factor Mafa and loss of beta cell identity. Activated B cells could also produce ROS that is deleterious to beta cell health.

Figure 3. Reactive-oxygen species (ROS) metabolism is important in many aspects of B cell function. ROS enhances the immune response and causes direct damage to pathogens and other cells that lack antioxidant capacity. Intracellular ROS modulates B cell function in many ways. (A) Upon B cell activation, BCR signaling triggers ROS production via the mitochondria and NADPH oxidase 1 (NOX1) complex. This ROS reversibly oxidizes tyrosine phosphatases to limit their ability to dephosphorylate target kinases. This action prolongs and enhances BCR signaling [104,108]. (B) Antigen internalization and presentation is an essential function of B cells and is modulated by production of ROS via NOX1. This production is key for the ability of antigens internalized via the BCR to be presented on the cell surfaces via Major-histocompatibility complex II (MHCII). Interestingly, ROS does not impact the presentation of intracellular derived antigens [103]. (C) After activation ROS opposes the capacity of B cells to secrete immunoglobulin. Nrf2 promotes IgM secretion by increasing antioxidant genes to oppose ROS [109]. (D) Both ROS and antioxidants that emerges from B cells impact bystander cells. B cells that present antigen to Tregs could transfer ROS to Tregs thus enhancing Tregs via the action of SENP3 and Bach2 [110]. Conversely, a B cell with enhanced antioxidant capacity may prevent ROS-mediated activation of SENP3 and thus inhibit Tregs. The action of B cells may also mediate tissue protection in cell types sensitive to ROS, like beta cells. Under certain circumstances B cells can upregulate antioxidant capacity that can be transferred to the extracellular space (green dots). This transfer prevents degradation of ROS-sensitive beta cell transcription factor Mafa and loss of beta cell identity. Activated B cells could also produce ROS that is deleterious to beta cell health.

Increased antioxidant capacity could also alter the antigen presenting role of B cells in T1D [103]. Many studies indicate that B-T cell interaction perpetuates autoimmunity [111]. B cells communicate with the T cell at the immune synapse via the Major-Histocompatibility Complex through presentation of antigen as well as accessory molecules, leading to mutual activation. ROS is also produced at this immune synapse and has significant consequences for T cell activation by inhibiting phosphatases and enhancing and prolonging intracellular signaling [112]. Whether this ROS can be impacted by antioxidant capacity of the individual APC is less well understood. Interestingly, in vitro studies indicate that ROS production by macrophages induces new Tregs in a ROS-dependent manner [113]. Other studies indicate that ROS stabilizes Foxp3 expression via SUMO-specific protease 3 (Senp3) activation and retention of Bach2 in the nucleus thus suppressing expression of T effector genes and maintaining Treg stability (Figure 3D) [110]. The presence of B cells with enhanced antioxidant capacity may reduce the amount of ROS that a docked Treg sees thus preventing stabilization of Foxp3 leading to loss of Treg stability or prevention of the induction of new Tregs. This metabolic counter-regulation may disrupt immune regulation in T1D. The many putative roles of ROS in B cells are outlined in Figure 3.

While there is very little direct evidence defining B cell metabolism in T1D, the response of B lymphocytes in T1D to treatment with immune therapies may offer clues to their metabolic regulation. Two therapeutics, anti-CD20 (Rituximab) and Imatinib (Gleevec), have been studied in recent onset T1D and both have been studied extensively in malignant hematopoietic disease where there are known metabolic requirements and consequences among the targeted cells that dictate treatment efficacy. Thus, the effectiveness or lack thereof in T1D may provide indirect insight into the metabolic state of B cells in T1D.

Anti-CD20 is the only B cell targeting therapeutic tested clinically in T1D to date [12,114]. In human clinical trials in new onset T1D, there was moderate protection from beta cell loss but beta cell loss resumed soon after therapy was discontinued [114]. This resumption was linked back to a reemergence of autoreactive specificities after therapy, as well as a loss of CD20 in B cells that infiltrated the pancreas [15,18]. This change in anti-CD20 expression was linked to activation induced by CD40-CD40L interactions, which targets the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [115,116].

Recently, c-Abl inhibitor Gleevec (imatinib mesylate) was found to reverse T1D in NOD mice [117]. The cellular and molecular mechanisms that provide this reversal are not well understood, although several studies have related it to a reduction of cellular stress at the level of the beta cell [118–120]. Work from our lab links this back to an increase in the antioxidant response in B lymphocytes that is passed on to the extracellular environment [107]. Enhanced B cell redox restored ROS-sensitive Mafa in beta cells leading to improved insulin secretion and restoration of euglycemia but only when B cells were present [107]. This interaction illustrates the potential for excessive antioxidant metabolism among B cells in T1D. This antioxidant phenotype is similar to that seen in the response of hematopoietic cancers that develop resistance to these cancer therapeutics [121,122]. Taken together these data indicate B cells in T1D may be uniquely adapted to handle metabolic stress, which in turn may provide resistance to therapy or tissue protection depending on the context. This adaptation may also underlie the development and survival of the autoreactive cells that initiate disease by protecting them from negative selection.

B cells may be targeted to alter development, to prevent activation, to prevent B cell-T cell interactions and antigen presentation, or to modify their metabolic state to allow for favorable functions or more successful immune depletion in combination with other B cell therapeutics. Current research suggests that the metabolic requirements of T and B cells are different, which provides an opportunity to target these subsets specifically but also could limit the impact of metabolic therapies given the dependence of disease on both cell types. Additionally, poor subset discrimination between regulatory and effector B cell subtypes prevents the elegant dissection of metabolic requirements for regulation versus effector function as has been achieved in T cells. When implementing metabolic therapies, unintended consequences could result on both regulatory and effector T and B cells, especially in diseases in which the interplay of these cell types have an important role like T1D.

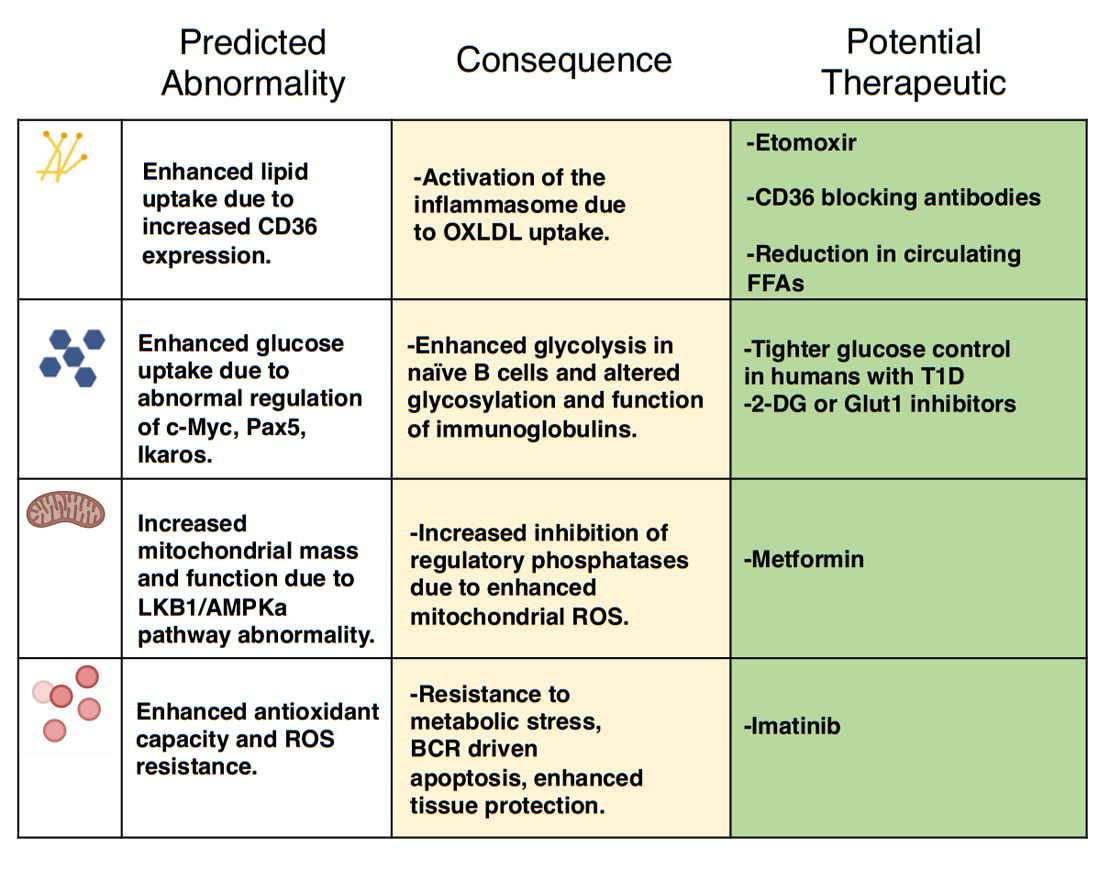

Virtually no research exists that directly assesses the metabolic state of B cells in T1D in mice or in humans. Analysis of the available evidence as presented in this review suggest that multiple metabolic defects in glucose uptake, mitochondrial dynamics, ROS metabolism, enhanced expression of lipid scavenger CD36, and enhanced fatty-acid uptake could contribute to abnormal B cell development, activation, or survival in T1D (Summarized in Figure 4). Additional research needs to be carried out to determine whether targeting these metabolic pathways could normalize B cell development, prevent survival of autoreactive B cells, inhibit auto-antigen presentation, or induce beta cell protection. The fact that metabolism plays an integral role in all of these pathways highlights the importance of understanding B cell metabolism in T1D.

Figure 4. Predicted metabolic abnormalities in B cells in T1D encompass multiple pathways with consequences on B cell function. Enhanced NF-ΚB signaling in NOD B cells may oppose the LKB1/AMPKa pathway, leading to increased mitochondrial mass and priming the cell to respond robustly to myriad metabolites. As B cell activation is dependent on mitochondrial remodeling, enhanced mitochondrial mass (“pre-activation”) could increase the metabolic fitness of autoreactive B cells and allow them to effectively generate ATP in areas of low nutrients. Enhanced c-Myc activity has been identified in lymphocytes from NOD mice. As c-Myc regulates glucose metabolism, an increase in c-Myc activity in B cells could increase Glut1 expression and glucose trafficking driving enhanced oxidative phosphorylation of glucose and glycolysis. This change could alter B cell function through enhanced metabolic fitness as well as alter the glycosylation patterns on immunoglobulins and cell surface proteins. B cells in NOD mice express enhanced lipid-scavenger CD36. This enhanced expression could increase utilization of fatty-acids, the main substrate of naïve B cells, thus improving survival. Additionally, CD36 capture of OXLDL immune-complexes could activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Finally, increases in metabolism increase ROS production, which could be detrimental to B cell survival and function. T1D B cells seem to possess enhanced antioxidant capacity to protect against ROS. Additionally, this property has been demonstrated to offer tissue protection by scavenging ROS in the islet-microenvironment and protecting ROS-sensitive transcription factors but may at the same time diminish Tregs, pointing to a careful balance needed for any metabolic therapy.

Figure 4. Predicted metabolic abnormalities in B cells in T1D encompass multiple pathways with consequences on B cell function. Enhanced NF-ΚB signaling in NOD B cells may oppose the LKB1/AMPKa pathway, leading to increased mitochondrial mass and priming the cell to respond robustly to myriad metabolites. As B cell activation is dependent on mitochondrial remodeling, enhanced mitochondrial mass (“pre-activation”) could increase the metabolic fitness of autoreactive B cells and allow them to effectively generate ATP in areas of low nutrients. Enhanced c-Myc activity has been identified in lymphocytes from NOD mice. As c-Myc regulates glucose metabolism, an increase in c-Myc activity in B cells could increase Glut1 expression and glucose trafficking driving enhanced oxidative phosphorylation of glucose and glycolysis. This change could alter B cell function through enhanced metabolic fitness as well as alter the glycosylation patterns on immunoglobulins and cell surface proteins. B cells in NOD mice express enhanced lipid-scavenger CD36. This enhanced expression could increase utilization of fatty-acids, the main substrate of naïve B cells, thus improving survival. Additionally, CD36 capture of OXLDL immune-complexes could activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Finally, increases in metabolism increase ROS production, which could be detrimental to B cell survival and function. T1D B cells seem to possess enhanced antioxidant capacity to protect against ROS. Additionally, this property has been demonstrated to offer tissue protection by scavenging ROS in the islet-microenvironment and protecting ROS-sensitive transcription factors but may at the same time diminish Tregs, pointing to a careful balance needed for any metabolic therapy.

While there is much more work to be done on the basic metabolic pathways in autoreactive B cells, there are emerging opportunities to advance understanding of immune metabolism in the clinical space. As suggested above, it may be readily hypothesized that treatment with anti-CD20 or imatinib could have metabolic consequences on B cells that may dictate the response to therapy, and this hypothesis could be explored in clinical trial samples. Likewise, therapies depleting T cells or other cell types could alter the types of stimulation that B cells receive which may impact their metabolism and change their sensitivity to metabolic therapy. Understanding the metabolic landscape induced by immune therapy is an outstanding opportunity to improve future approaches to the treatment of T1D. At the same time, understanding how immune metabolism changes across cell subsets as people progress towards type 1 diabetes, such as in the T1D TrialNet, will be invaluable to understanding the impact of immune metabolism on autoimmunity and in identifying future treatments. As it is becoming clear that metabolism is intricately complexed to the effector function in hematopoietic cells, it needs to be addressed whether cellular metabolism will provide a more predictive biomarker of disease progression and therapeutic responses. Despite the many remaining unknowns, there are clear clues to the role of metabolism in B cells in T1D that present an opportunity awaiting further exploration and implementation. Figure 5 summarizes the putative metabolic abnormalities in B cells in T1D, the potential consequences, and the therapeutic options available to augment these processes. As data become available in T1D we anticipate that future approaches will specifically target these metabolic pathways directly for treatment and will use these metabolic readouts to predict responsiveness to immune therapies in T1D clinical trials.

Figure 5. The putative differences in B cell metabolism in T1D, their effects, and potential therapeutic opportunities. This figure illustrates predicted differences in B cell metabolism in T1D, their consequence on normal B cell function, and the potential therapeutic interventions that may alter these metabolic parameters to protect from disease.

Figure 5. The putative differences in B cell metabolism in T1D, their effects, and potential therapeutic opportunities. This figure illustrates predicted differences in B cell metabolism in T1D, their consequence on normal B cell function, and the potential therapeutic interventions that may alter these metabolic parameters to protect from disease.

CSW and DJM researched, wrote, and edited this review.

The authors declare no conflict of interest

DJM was supported by a Career Development Award from the JDRF and by the Thomas J. Beatson Jr Foundation Grant #2019-016.

Figures were created with Biorender.com.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

95.

96.

97.

98.

99.

100.

101.

102.

103.

104.

105.

106.

107.

108.

109.

110.

111.

112.

113.

114.

115.

116.

117.

118.

119.

120.

121.

122.

Wilson CS, Moore DJ. B cell Metabolism: An Understudied Opportunity to Improve Immune Therapy in Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes. Immunometabolism. 2020;2(2):e200016. https://doi.org/10.20900/immunometab20200016

Copyright © 2020 Hapres Co., Ltd. Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions